The edge of the city is full of graveyards, since new ones are rarely built inside the city. And after Day of the Dead, orange flowers drying on the graves were the typical adornment of the graveyards, like the desolation after a party, with empty bottles and plastic bags scattered on the ground. Some of the graves have various new crosses tied to them according to the custom of returning to the grave and tying a new cross on it on the first, second and third anniversaries of death. The rusting of the crosses and decay of gravestones is like the slow corrosion of memory and pain.

I had started on the Day of the Dead partially from superstitious reasons. I knew that arriving on the Day of the Dead would probably be a bad omen, so starting on the day of the Dead hopefully would have the opposite effect. And the graveyards with their flowers in vases made of cola bottles held a melancholy fascination for me, as did the little white crosses along the highways marking where accidents had taken place. Sometimes I would see clusters of several crosses in the verge of a highway and looking at the names would see that a whole family had died in a traffic accident, parents and children all. And such ordinary spots would be infused with sadness.

I approved of the tradition of the crosses and wondered whether I too would have some little cross with my name on it, if I were to be run over on a secondary highway with a blind curb.

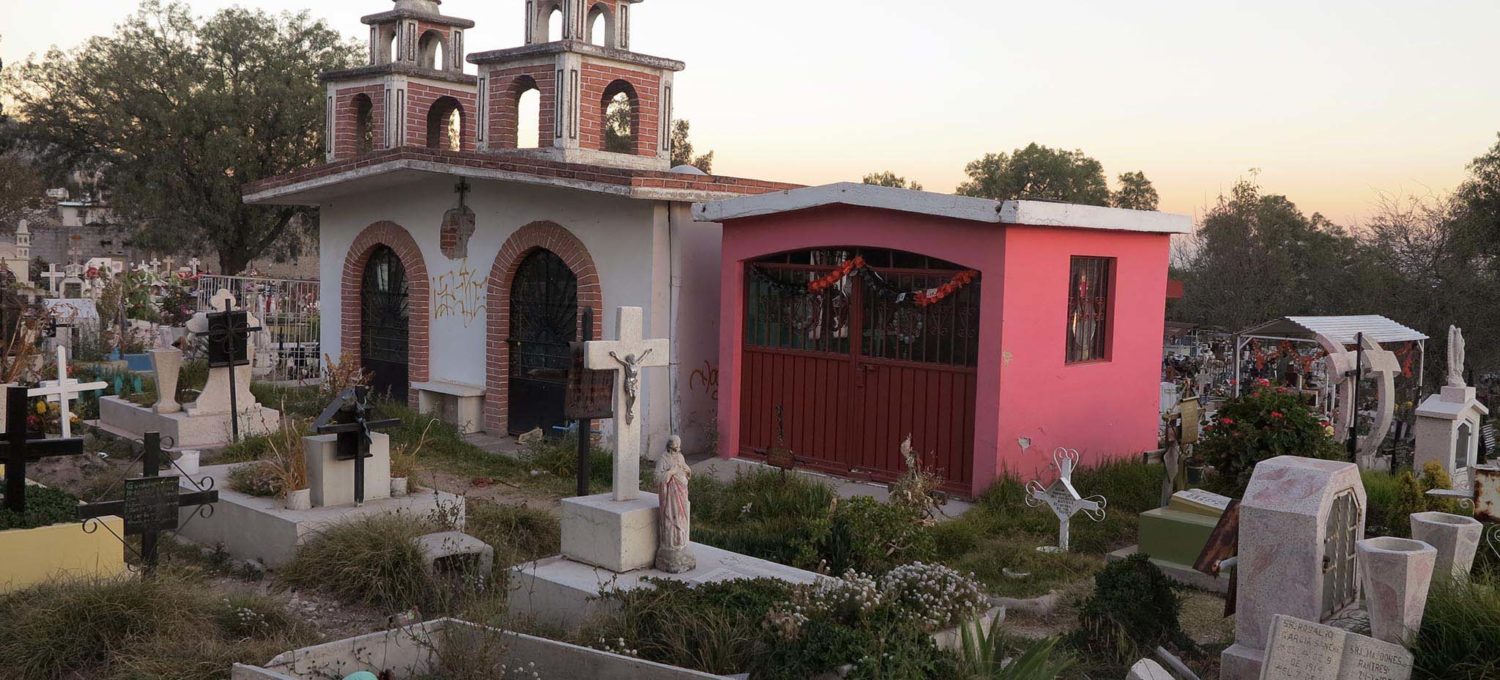

As I zigged and zagged along the Cerro del Pino I came across a small graveyard overlooking the city. Gravestones descended along the incline, crooked, crumbling in the small plot of land on the hillside The tombs were not very old and they were all very different looking, some massive and baroque, others simple and spare. Crosses of all types, from marble slabs to two planks nailed together a grab bag of architectonic shapes. Fields lay up the hill behind it.

I saw a man in a straw hat with a teenage assistant sitting in a shed next to the fence separating the graveyard from the end of the road. They were taking a break from cleaning the paths between the graves.

He told me he had come from Oaxaca some thirty years ago and he had recently gotten this job. Everybody in the south of the city seemed to have come from Oaxaca. Having heard of other graveyards that were haunted I asked him whether he had ever seen any ghosts. He said no, here the dead were at peace. Nor was there any graffiti on the graves.

The biggest problem was people stealing from the graves. Items from graveyards could be used in witchcraft and occasionally crosses or images left with the crosses would go missing, stolen for their magical properties. He did not know how they were being used, though he looked somewhat worried. It would not do for a graveyard to have a reputation as a place where grave robbery took place.

I had once spoken to a witch in Iztapaluca, the aunt of a friend, and she had told me about her excursions into the graveyards of Mexico City, seeking signs that they had been tampered with and undoing the spells she found around them, until she had become afraid and stopped. She said some of the dead were lonely. When a black magician came upon a grave which nobody was caring for he would bribe the dead soul with offers of attention, such as a mass, in return for assistance in the worldly business of curses and blessings.

This graveyard on the hill seemed quiet enough though.

I left the man and his assistant to their work on the peaceful slope and cut along a ravine to the north among the self-built houses teetering along its ledges.